Fast Owen-scrambling of Arrays

Different ways to randomly permute implicit trees in O(n) time

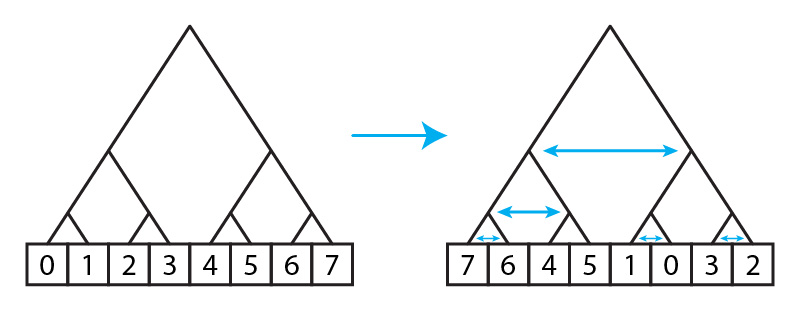

Say you have an array whose length is a power of some base b. For most of this post we’ll be using powers of two, but we’ll discuss other bases as well. Imagine that there is a b-ary tree over the array. We want to shuffle the array in the following way: randomly shuffle the b sub-trees of the root. Then, recurse into each subtree, and do the same, until we get to the bottom.

Here’s a simple recursive C++ function to do this for a binary tree (b=2):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

// Note this function only works if length is a power of two.

template<typename T>

void binary_tree_shuffle(T* arr, int length) {

if (length == 1) return;

bool swap_subtrees = get_random_bit();

if (swap_subtrees) {

for (int i = 0; i*2 < length; i++) {

std::swap(arr[i], arr[i+length/2]);

}

}

binary_tree_shuffle(arr, length/2);

binary_tree_shuffle(arr+length/2, length/2);

}

Typical caveat here: I haven’t tested this code, it might not even compile, it’s just to give an idea.

Owen-scrambling, Faure-Tezuka scrambling

This sort of recursive tree shuffling is known as “Owen-scrambling”, or Owen’s scrambling, because it was introduced by Art Owen in the paper “Randomly permuted (t,m,s)-nets and (t, s)-sequences” (1995). Actually I think it was introduced by Owen in 1994 in a technical report, but that’s not what most papers cite. Anyway Owen also calls it “Nested uniform scrambling”, which is probably a better name, but less commonly used.

Typically Owen-scrambling is done on points that are placed within the unit interval [0, 1). When it’s done on an array, it’s sometimes called Faure-Tezuka scrambling, because Henri Faure and Shu Tezuka proposed this in “Another random scrambling of digital (t,s)-sequences” (2002). But this terminology is also ambiguous because Faure and Tezuka mentioned both this type of shuffling, and a different type of shuffling based on matrix multiplications, in the same paper. And usually, but not always, when academics say “Faure-Tezuka scrambling”, they mean the matrix one.

Performance

This recursive algorithm pretty clearly takes O(n*log(n)) time, where n is the length of the array. Another common way to do this is with a “permutation tree”, which is also O(n*log(n)).

It might be surprising, but it’s actually possible to do this in O(n) time, assuming you can generate a good random integer in O(1) time.

In fact, there are at least three different ways to do this! Maybe it’s overkill, but I’m going to discuss all three in this post.

Background

Let’s back up. Who even cares about this? Why is it useful? I’m not going to go into a ton of detail on this, but Owen-scrambling in general is a really nice way to randomize points that are well-distributed. Owen-scrambling arrays can be used to Owen-scramble a fixed number of random points in the unit-interval, by putting each point into its own cell in the array.

More importantly, it’s a useful method to shuffle the order of some progressive sample sequences, specifically (t,s)-sequences. A (t,s)-sequence shuffled with this method is still a (t,s)-sequence, but will be decorrelated from other shufflings of it. The personal background here is that I worked on a paper, and we discussed this kind of shuffling in Section 5.2 of the paper, but we never discussed how to do it efficiently. To be honest, other than the hashing technique I’ll mention first, I hadn’t precisely figured it out. I knew it was possible, but it was sort of a loose end.

Slight restatement: getting a shuffled index array.

We’re going to slightly adjust this problem to make further discussions simpler, but it’s basically the same. Rather than shuffling an array in-place, all we’re going to look at is generating a shuffle array of indices, which could then be used to shuffle some other array. Using the original shuffle, we’re now defining a function get_base2_shuffled_indices().

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

// Note this function only works if length is a power of two.

vector<int> get_base2_shuffled_indices(int length) {

vector<int> indices(length);

// Could also use std::iota.

for (int i = 0; i < length; i++) indices[i] = i;

// Call our earlier function.

binary_tree_shuffle<int>(indices.data(), length);

return indices;

}

Method 1: Laine-Karras Hashing

If your base is 2, it turns out that you can do this really fast with some clever hashing. I won’t go into too much detail, because it’s covered so well elsewhere. I recommend checking of Brent Burley’s paper “Practical Hash-based Owen Scrambling” (2020), and also this blog post is great and improves upon Burley’s hash function. The technique is called Laine-Karras hashing because the idea was introduced in “Stratified Sampling for Stochastic Transparency” (2011) by Samuli Laine and Tero Karras.

The code looks something like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

// Note this function only works if length is a power of two.

uint32_t laine_karras_permutation(uint32_t x, uint32_t seed) {

x += seed;

x ^= x * 0x6c50b47cu;

x ^= x * 0xb82f1e52u;

x ^= x * 0xc7afe638u;

x ^= x * 0x8d22f6e6u;

return x;

}

uint32_t reverse_bits(uint32_t x) {

x = (((x & 0xaaaaaaaau) >> 1) | ((x & 0x55555555u) << 1));

x = (((x & 0xccccccccu) >> 2) | ((x & 0x33333333u) << 2));

x = (((x & 0xf0f0f0f0u) >> 4) | ((x & 0x0f0f0f0fu) << 4));

x = (((x & 0xff00ff00u) >> 8) | ((x & 0x00ff00ffu) << 8));

return ((x >> 16) | (x << 16));

}

uint32_t shuffle_index(uint32_t idx, uint32_t seed) {

idx = reverse_bits(idx);

idx = laine_karras_permutation(idx, seed);

idx = reverse_bits(idx);

return idx;

}

vector<uint32_t> get_base2_shuffled_indices(int length) {

vector<uint32_t> indices(length);

uint32_t seed = get_random_uint32(0, length);

for (uint32_t i = 0; i < length; i++) {

indices[i] = shuffle_index(i, seed) % length;

}

return indices;

}

This hashing is a great technique that will probably be suitable for a lot of applications. I should be a little honest, it’s not really O(1), because of the reverse_bits operation, which is actually O(log log n). If you moved up to 64-bit integers, for example, you would have to add one line of code to that function (in addition to modifying the masks and everything.

Anyway there’s one area that the hashing isn’t great for, which is bases other than two.

Method 2: Subtree Permutations

This next idea I think is going to be a little bit slower than Method #3, although I’m not sure. It may be a bit trickier to generalize to other bases. That being said, I think it’s more intuitive, and it can also be done sequentially with O(1) persistent memory (i.e. you don’t need to store the entire shuffled array, only the last permuted index).

To give the intuition for this, let’s imagine we have an array of 8 items and we’re doing the shuffling in base 2. We want to get the value of the first shuffled index in the array. Since this can randomly come from any value in the original array, we can just generate any random number from 0 to (and including) 7. Now, we can observe that the second item in the array will, before and after shuffling, have the same parent in the tree. So they must share all the same digits (bits for a binary tree), except for the last digit. The third item in the array will share the same grandparents as the first two items. That means the first digit will be the same as for the first two indices, the second digit will be different, and the last (third) digit will be chosen randomly. The fourth point shares the same parent as the third point, so the first two digits will be the same, and the last digit will be flipped.

The idea here is that we start out by generating a random number for the first shuffled index. From then on, for each new shuffled index, we find the least significant digit for which the new index is zero, while the previous index was one. And we only need to generate a new random number for the “subpath” below that digit. Here’s what the code looks like:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

vector<uint32_t> get_base2_shuffled_indices(int length) {

vector<uint32_t> indices(length);

indices[0] = get_random_uint32(0, length);

int prev_idx = 0;

for (int next_idx = 1; next_idx < length; next_idx++) {

int changed_bit = 1;

// Find the shared ancestor with the previous index.

while (!(next_idx & changed_bit) || (prev_idx & changed_bit)) {

changed_bit <<= 1;

}

// Flip the bit for the opposite subtree.

int next_shuffled_index = indices[prev_idx]^changed_bit;

if (changed_bit > 1) {

// Randomize the remaining subpath.

next_shuffled_index ^= (get_random_uint32(0, length) & (changed_bit-1));

}

indices[next_idx] = next_shuffled_index;

prev_idx = next_idx;

}

return indices;

}

Wait, what about that internal while loop? Well, the observation here is that 50% of the time, we won’t even enter that loop. 25% of the time, that loop will have one iteration. 12.5% of the time, it will have two iterations, etc. So on average, there will be only one iteration. Which means that this whole algorithm is still O(n) time. That being said, there are some different ways you could avoid the loop. I think one way in base-2 would be to use a compiler intrinsic to find the least significant 1-valued bit of ((next_idx^prev_idx) & next_idx).

I’m not 100% sure but I think this can be generalized to higher bases, and still be O(n) time. The main thing you need to be careful about is the “changed_bit”. Now you have multiple choices for the new bit. But I think you can do it with a little cleverness, and the bookkeeping would be easier using Kensler’s permute() function.

Method 3: Stochastic Generation Inversion

In most code, I would prefer either Method 3 or Method 1 to Method 2. I think Method 3 is the fastest, but has the downside that you aren’t shuffling the points in order, and it’s less intuitive and harder to understand than Method 2.

The idea is building directly off our paper “Stochastic Generation of (t,s) Sample Sequences” (Helmer, Christensen, Kensler 2021), specifically section 3.3. In that section we describe a method to generate an Owen-scrambled van der Corput sequence by progressively subdividing the unit interval, and generating random points in opposite sub-intervals from previous points. This is Listing 1 from that paper:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

// Listing 1: C++ code to generate a stratified 1D sequence,

// identical to the Owen-scrambled base-2 van der Corput sequence.

void get1DSamples(int nSamples, double samples[]) {

samples[0] = drand48();

for (int prevLen = 1; prevLen < nSamples; prevLen *= 2) {

int nStrata = prevLen * 2;

for (int i = 0; i < prevLen && (prevLen+i) < nSamples; i++) {

int prevXStratum = samples[i] * nStrata;

samples[prevLen+i] = ((prevXStratum^1) + drand48()) / nStrata;

}

}

}

Now let’s say we want to adapt that to generate array indices. We can do basically the same thing with integers. This does not solve our problem, it’s just the first piece.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

vector<uint32_t> get_stratified_integers(int length) {

vector<uint32_t> randomized_indices(length);

randomized_indices[0] = get_random_uint32(0, length);

for (int prev_len = 1; prev_len < length; prev_len *= 2) {

for (int i = 0; i < prev_len && (prev_len+i) < length; i++) {

randomized_indices[i+prev_len] =

(randomized_indices[i] ^ interval_width)

^ (get_random_uint32(0, length) & (interval_width - 1));

}

interval_width /= 2; // Or interval_width >>= 1, if you prefer.

}

return randomized_indices;

}

So let’s clarify what this actually does. Let’s say our length is 16. The first value will be any random number from 0 to 15. If the first value is in the range [0, 7], the second value will be in the range [8, 15], or vice versa. Then, if the first value is say, in the range [4,7], the third point will be in the range [0,3]. In other words, it recursively chops the array into halves, and it randomly places each new index in the smallest opposite sub-interval of the previous point, in order.

Now, if we replace the get_random_uint32(0, length) call with the value of 0, we get a sort of “unshuffled” version of this. For 16 points, we would get, in order: 0, 8, 4, 12, 2, 10, 6, 14, 1, 9, 5, 13, 3, 11, 7, 15. You can see that it’s flipping first the most significant bit, then it’s iterating over previous points, and flipping successively less significant bits. The randomized version is actually doing the same thing, but with the less significant bits being randomized at each point.

So what we need to do is to reindex the randomized array using the unrandomized array. In other words, if we look up the 0th value and the 8th value in the randomized array, we know that they differ in only the least significant digit. The same for the 4th value and the 12th value. But we know that the 0th value and 4th value differ in the second most significant digit, and the same for the 8th and the 12th value. So the 0th, 8th, 4th, 12th values will form a valid permutation.

Here’s what the final code looks like:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

vector<uint32_t> get_base2_shuffled_indices(int length) {

vector<uint32_t> randomized_indices(length);

vector<uint32_t> bit_reversed_indices(length);

bit_reversed_indices[0] = 0;

randomized_indices[0] = get_random_uint32(0, length) % length;

int interval_width = length / 2;

for (int prev_len = 1; prev_len < length; prev_len *= 2) {

for (int i = 0; i < prev_len && (prev_len+i) < length; i++) {

bit_reversed_indices[i+prev_len] =

(bit_reversed_indices[i] ^ interval_width);

randomized_indices[i+prev_len] =

(randomized_indices[i] ^ interval_width)

^ (get_random_uint32(0, length) & (interval_width - 1));

}

interval_width /= 2; // Or interval_width >>= 1, if you prefer.

}

// We reindex the array by itself, using the randomized indices.

for (int i = 0; i < length; i++) {

bit_reversed_indices[i] = randomized_indices[bit_reversed_indices[i]];

}

return bit_reversed_indices;

}

The obvious downside here is we need to allocate that second array. But I think it’s still sort of a cool little trick, and I haven’t tested performance yet, but I think it should run quite fast even if you’re doing the whole thing in a different base. It may not be immediately obvious how to generalize this to a higher base, but we go over that to some degree in Section 4.6 of the paper. Hopefully I’ll have some code up online for arbitrary bases in the not too distant future.

References

- Art Owen. “Randomly permuted (t,m,s)-nets and (t,s)-sequences”. Monte Carlo and Quasi-Monte Carlo Methods in Scientific Computing. Ed. by Niederreiter, H. and Shiue, P. Springer, 1995, 299–317.

- Henri Faure and Shu Tezuka. “Another random scrambling of digital (t,s)-sequences”. Monte Carlo and Quasi-Monte Carlo Methods 2000. Ed. by FANG, K.-T., Niederreiter, H., and Hickernell, F. Springer, 2002, 242–256.

- Samuli Laine and Tero Karras. “Stratified sampling for stochastic transparency”. Computer Graphics Forum (Proc. Eurographics Symposium on Rendering) 30.4 (2011)

- Andrew Helmer, Per Christensen, and Andrew Kensler. “Stochastic Generation of (t,s) Sample Sequences”. Eurographics Symposium on Rendering - DL-only Track. Ed. by Bousseau, A. and McGuire, Morgan, 2021.